“Persuasion is the centerpiece of business activity.”

“Story Telling That Moves People,” Harvard Business Review, June 2003: 1

Free sampling is an age old marketing tactic that often arises from the idea that a customer first needs to try a product to reduce the future risk of spending money to buy it. McDonald’s is currently using this tactic to get its customers to try its new line of Mocha coffees (good through August 3rd by the way).

But as Robert Cialdini points out in his classic book Influence: The New Psychology of Modern Persuasion, trial tactics may actually carry a much deeper psychological connection that can help you sell more product via the concept known as reciprocation.

In short, Cialdini describes reciprocation as follows:

The rule says that we should try to repay, in kind, what another person has provided us. If a woman does us a favor, we should do her one in return; if a man sends us a birthday present, we should remember his birthday with a gift of our own; if a couple invites us to a party, we should be sure to invite them to one of ours. By virtue of the reciprocity rule, then, we are obligated to the future repayment of favors, gifts, invitations, and the like.

Cialdini also goes on to describe how the rule is so powerful as a social construct that it can even create situations where the rule often produces a “’yes’ response to a request that, except for an existing feeling of indebtedness, would have surely been refused” and where “people we might ordinarily dislike – unsavory or unwelcome sales operators, disagreeable acquaintances, representatives of strange or unpopular organizations – can greatly increase the chance that we will do what they wish merely by providing us a small favor prior to their requests.”

Think about this! Cialdini asserts that you can persuade somebody to do something you want despite your request being one that the person would otherwise normally refuse or may be from somebody the person may not or does not even like.

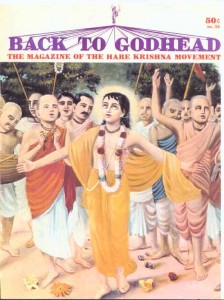

Which brings us to Cialdini’s observations and examples of the Hare Krishnas. He describes how the Krishnas, an Eastern religious sect comprised of “devotees – often with shaved heads, and wearing ill-fitting robes, leg wrappings, beads and bells” successfully grew in the number of followers as well as in wealth and property in the United States during the 1970’s. He sets the situation for the successful reciprocation tactics that helped this group amass wealth by stating “The average American considered the Krishnas weird, to say the least, and was reluctant to provide them money to support them.”

So what did the Krishnas do to overcome this negative bias?

The Krishnas’ resolution was brilliant. They switched to a fund-raising tactic that made it unnecessary for target persons to have positive feelings towards fund raisers. They began to employ a donation-request procedure that engaged the rule for reciprocation, which … is strong enough to overcome the factor of dislike for the requester.”

The … strategy … involves the solicitation of contributions in public places with much pedestrian traffic (airports are a favorite), but now, before a donation is requested, the target person is given a “gift” – a book (usually the Bhagavid Gita), the Back to Godhead magazine of the society, or, in the most cost-effective version, a flower. The unsuspecting passerby who suddenly finds a flower pressed into his hands or pinned to his jacket is under no circumstances allowed to give it back, even if he asserts he does not want it. “No, it is our gift for you,” says the solicitor, refusing to accept it. Only after the Krishna member has thus brought the force of the reciprocation rule to bear on the situation is the target asked to provide a contribution to the society. This benefactor-before-beggar strategy has been wildly successful for the Hare Krishna Society, producing large-scale economic gains and funding for the ownership of temples, businesses, houses, and property in 108 centers in the United States and overseas.”

The natural lesson here is for marketers who develop “free sample” programs. Cialdini addresses this directly with the following:

As a marketing technique, the free sample has a long and effective history. In most instances, a small amount of the relevant product is provided to potential customers for the stated purpose of allowing them to try it to see if they like it. And certainly this is a legitimate desire of the manufacturer – to expose the public to the qualities of the product. The beauty of the free sample, however, is that it is also a gift and, as such, can engage the reciprocity rule. In true jujitsu fashion, the promoter who gives free samples can release the natural indebting force inherent in a gift while innocently appearing to have only the intention to inform. A favorite place for free samples is the supermarket, where customers are frequently provided with small cubes of a certain variety of cheese or meat to try. Many people find it difficult to accept a sample from the always-smiling attendant, return only the toothpick, and walk away. Instead, they buy some of the product, even if they might not have liked it especially well.”

I suspect McDonald’s knows this all too well. By offering free samples of its Mocha and Iced Mocha beverages within its stores, it’s highly likely that the taster will also buy additional food. I also suspect that Monday was selected as a day of the week where sales are normally not as strong as other days of the week.

At the end of the day, that is the role of the marketing manager: to persuade people to become customers and to buy your products and services. I highly recommend that you read (or re-read) Influence: The New Psychology of Modern Persuasion to gain additional insights into how you can refine your persuasion skills.

P.S. Reading about Krishnas at the airport always reminds me of this scene from the 1980 movie Airplane. Enjoy!